“Man Belongs To The Earth”

One of the more egregious misrepresentations of Native Americans at Expo ‘74 was front and center at the United States Pavilion. In the US Pavilion’s inner courtyard, a wall towered over fair visitors. On it were the words, “THE EARTH DOES NOT BELONG TO MAN, MAN BELONGS TO THE EARTH.” Several totem poles were arranged in front of the wall.

The IMAX film made for the U.S. Pavilion was similarly titled “Man Belongs To The Earth.” In American Cinematographer magazine, the title was explained this way: “The title of this film is drawn from a speech made by Chief Seattle of the Suquamish Tribe when the Federal Government offered to purchase his tribal lands in 1854. The words were chosen because they epitomize the attitude of our country’s first environmentalists, the American Indians, and suggest that we should return to this way of thinking.”

In reality, Chief Seattle did make a speech to government officials at a meeting in or around 1854, and that is about as much of this story as can be reasonably verified. In 1887, Henry A. Smith wrote down what he believed Chief Seattle to have said 33 years earlier, which probably would have been translated into English from Lushotseed by way of Chinuk Wawa. This secondhand remembered version would be modified and reprinted many times over the years, often with tweaks to make it better suit the message intended by the person quoting it.

In 1972, an environmentalist movie called Home needed a promotional poster, so screenwriter Ted Perry used Chief Seattle’s speech as a starting point for a fictional message from an unspecified fictional Native American. Perry added extensive environmentalist material that was nowhere to be found in the original version written down by Smith. The material added by Perry in 1972 included the statement, “the Earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the Earth.” Later, the film’s producer added more religious messaging to the speech (the film was sponsored by the Southern Baptist Radio and Television Commission) and removed the attribution to Perry, creating the impression that this new “environmental version” was what Chief Seattle had said.

In other words, fair-goers were urged to return to a “way of thinking” that was not the stated philosophy of Chief Seattle or any other indigenous person, past or present. It had been made up two years earlier by a white screenwriter named Ted to help sell a movie. Although it is easier to discover that fact today with the help of the internet, a bit of help from a contemporary historian would have made it clear that this version of the speech was a very recent and historically inaccurate addition to the Chief Seattle canon. As noted in the National Archives page on the speech, “The purported letter by Chief Seattle to President Pierce is very likely spurious. Among other charges, it denounces the White Man's propensity for shooting buffaloes from the windows of the ‘Iron Horse’—a remarkable observation by Seattle, who never in his lifetime left the land west of the Cascade Mountains and thus never saw a railroad and may never have seen a buffalo, either.”

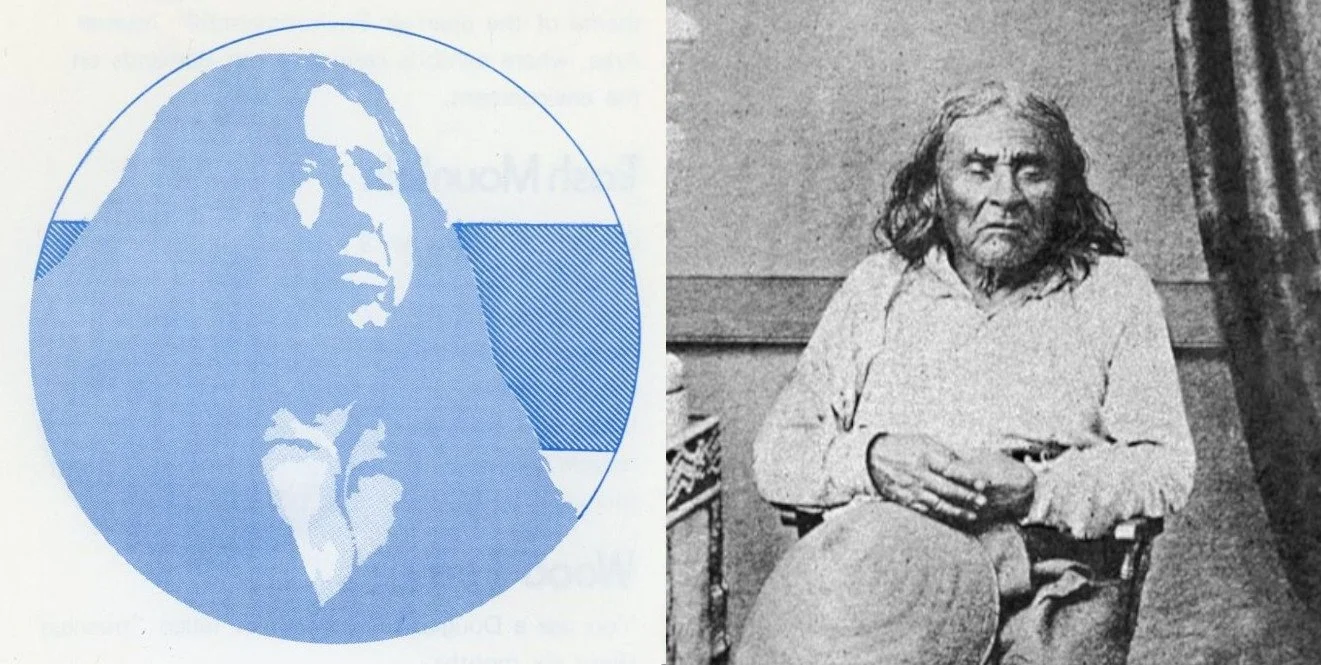

“The earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the earth” has taken on a life of its own, and you can still buy posters, t-shirts, stickers, mugs, and all other sorts of merchandise with the motto today. As there is only one known photo of Chief Seattle, and it is apparently not appealing enough to sell merch, many of these tchotchkes illustrate the “quote” with portraits of generic Native men in warbonnets or (in at least one case) Sitting Bull. To better suit modern perceptions of the word “man” as less than universal, some sellers have reworked the quote to be “Earth does not belong to us, we belong to the Earth.” The tradition of inventing words to put in Chief Seattle’s mouth is likely to carry on for many decades to come, evolving to suit the agenda of anyone who cares to borrow it. Fifty years from now, perhaps Chief Seattle’s “speech“ will be warning us that Mars does not belong to humans, humans belong to Mars.

The definitive resource on this topic is Eli Gifford’s 2015 book, “The Many Speeches of Chief Seattle (Seathl): The Manipulation of the Record on Behalf of Religious, Political and Environmental Causes.” It includes extensive sources and thoughtful analysis. It also includes a foreword from Ted Perry affirming the origins of the “environmental speech.” There is a genuine historical ambiguity around the accuracy of Smith’s initial reporting of Chief Seattle’s speech, which Gifford unpacks well, including discussing Smith’s own political motives and context for bringing the speech up when he did.

However, there is no historical ambiguity around the “environmental speech” or the saying “Earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the Earth.” Chief Seattle never said this. But at Expo ‘74, “on the way out of the [U.S.] pavilion, the visitor could view a 'talking mannequin' of Chief Seattle, proclaiming that 'the earth does not belong to man.'" (From The Fair and the Falls, p. 487.) The mannequin “talked” by having a video recording projected onto its face and audio playing nearby, much like the singing busts at the Haunted Mansion at Disneyland. It is hard to think of a more apt metaphor for how the environmental movement of the 1970s (and the U.S. Pavilion by extension) misappropriated Chief Seattle’s true image and words.

Left: Portrait on back cover of U.S. Pavilion brochure, where it was accompanied by other spurious Chief Seattle “quotes.”

Right: Only known photograph of the real Chief Seattle.