Washington State Pavilion Film: “About Time”

From “Film At Expo 74,” American Cinematographer (October 1974):

Running [Man Belongs To The Earth] a close second in terms of dramatic impact is the Washington State Pavilion’s presentation of “ABOUT TIME,” a color motion picture backgrounded with an original musical score. Using a rear screen projection technique, in conjunction with strategically-located mirrors, the production surrounds the viewer with sight and sound. The mirros, placed along the sides of the screen, give the impression of images stretching to infinity.

The film’s theme deals with man’s inter-relationship with time and his environment. It is presented inside a handsome new structure which houses a theatre and an exhibition hall with a grand mall in between.

From “About Time,” American Cinematographer (October 1974), by Rob Marona, producer:

Nothing warms a filmmaker’s heart more than the sight of long lines of people waiting anxiously to see a film to which he and his partner/director have dedicated two years of their lives. Happily, our latest film is playing to capacity crowds at the newest World’s Fair, EXPO ‘74.

Prior to winning this assignment, we spent twelve months in an unsuccessful attempt to get our first full-length feature into the works. I’m not so sure that the frustration of that experience didn’t play a major role in our approach to “ABOUT TIME,” the name of our new film for EXPO.

We wanted to entertain people, to motivate them and most of all, we wanted to do a feature. So, when the State of Washington came to us for a concept for their pavilion at EXPO ‘74, we strongly recommended a major film effort. Ed deMartin, my partner in filmmaking, and I were still in a “feature” frame of mind, but I don’t believe it was a conscious act on our part to make a 20-inute feature film, suitable for a fair-going audience! Yet, if I had to categorize “ABOUT TIME,” I’d call it a “mini-feature.”

A news release about the plans for “About Time” and the Washington State Pavilion can be viewed at WorldsFairPhotos.com.

The central theme for the World Exposition, “Man and His Environment,” stressing the many facets of ecology confronting our world today, is a timely theme, and one future outcome hoped for by the EXPO Commission is that the EXPO site will become a permanent meeting center for environmental study and planning. We reasoned that the fair would abound in anti-pollution technology and prognostications as to what the future holds for the Earth… and so we elected to avoid a documentary or an educational approach. Instead, we took a less traveled road, dealing with a specific aspect of “Man and His Environment” - that of man caught in the “time squeeze” - a theme we felt could offer both dramatic impact and entertainment value.

The State of Washington, as the host of EXPO ‘74, to be held in Spokane, Washington, was most anxious to make a very favorable impression, to display its largely unspoiled beauty and grandeur for all the world to see.

The friendly rivalry between Spokane, the urban center for the eastern half of the state, and Seattle, the western cultural center, was an added incentive to the men who conceived the fair. They knew that everyone would be comparing their efforts to the successful “CENTURY 21” Exposition, which Seattle hosted in 1962.

(Original Caption) Gas-powered wind machine (at right) is used during filming of key scene in the film: the two-year-old Jessica turns in a field as, as she does so, evolves into Jessica, aged five, by means of a dissolve.

Intensive scouting trips throughout the state made it quite evident that Washington was, indeed, a microcosm of Earth itself, bordered on the entire west coast by the ocean, and comprised of many inland streams and lakes, snow-capped mountains, desert flats and a jungle-like Rain Forest. Tempting as a “grand travelogue” was, we averted that trap and decided that the versatile beauty of the state would be ever present, but as a stage-set background, against which a dramatic story would unfold.

BEHIND THE CAMERA. The screenplay was based on an original story by Ed deMartin, who also directed the film. In his desire to emphasize the passage of time in the limited twenty-minute span allotted to the film, a dramatic device was required that would seem to span millennia. We elected to tell a story with a beginning, a middle and an end, confining our point-of-view to one aspect of man’s struggle with his environment: that of his mad dash to ever-compress Time to a point where he suffers a time “implosion”… where time can be compressed no longer, without devastating results. (The frightening implications of this phenomenon were dramatically presented in Alvin Toffler’s book, “Future Shock”.)

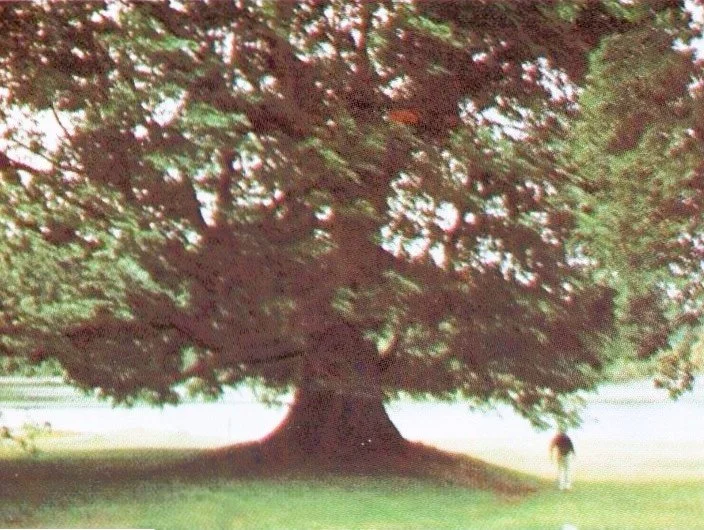

To compress time in our film we chose to show the cycle of development of a new-born baby growing to maturity Her life is portrayed against that of the other main “character” in the film, an ancient tree which, we imply, has been there before man was present on earth. The contrast between the two would become a vital vehicle through which the message of the film would be established. The tree selected, after many months of searching the entire state of Washington, was in fact, “only” 300-400 years old, with a spread of 125 feet and a trunk circumference in excess of 24 feet. It is a Big Leaf Maple (Acer Macrophyllm), which lives in Friday Harbor, in the San Juan Islands. It projected all of the strength, character and mystique that “Jessica,” the little girl in our story, believed was “the pace where God lived.”

The five girls chosen to play Jessica, the central character of the story, in various stages of growth were, as were all main characters, selected from some 500 cast candidates interviewed, all residents of the State of Washington.

“ABOUT TIME,” then, is concerned with Man and Earth. It is structured in three sequential “time cycles,” or acts.

“Before Time” (Time Cycle one)

“The intention of this segment was to create an impression of nature before humanity. The mood, one of mystery and beauty, moves with the basic flow of early life forms - from water, inland. We imply that Nature came first, and that it holds answers to timeless questions Man is not yet here to ask. This First Act ends by establishing an important, specific, physical presence: one of Nature’s finest creations… a magnificent, ageless Tree. The tree is a significant story element: it is the focal point of our movie. It is both a physical location, which provides filming continuity and progression, and a Symbol of Nature, around which the plot line generates.”

(Original Caption) Shooting in the super-dense Hoh Rain Forest, where the biggest problem was getting enough light to film effectively. Production crew lucked out on the often-rainy weather in Washington, and the sun stayed with them during most of the shooting.

“Time Being” (Time Cycle two)

“In this act, we introduce our second important physical presence, another of Nature’s finest creations… a beautiful child. The child is a Symbol of Humanity, and through her we see the affinity and affection that humans, during their earliest stages of development, have for Nature. To the child, the Tree is the most awesome living thing she has ever experienced - it is immense, strong, protective, constant, beautiful - and truly an expression of God. But, as the child grows, she drifts away from the natural things she instinctively loves. Through the demands of her inherently more sophisticated life form, she gradually becomes a creature of technology… a being of time. The Second Act ends with an insight which the child, (older now), experiences, while captured in a totally man-made, synthetic environment, which is in dramatic contrast to her (and humanity’s) natural origins. The child realizes that Man, influenced by the imposed restrictions of his individually limited time, is too often at odds with Nature… too often destructive of the things that matter most in life.”

“Beyond Time” (Time Cycle three)

“The Third Act is intended to create a romantic, timeless quality and mood. It means to appeal to the feelings of nostalgia, the simple need for natural beauty, and for an appropriate sense of the human values essential to us. The child becomes a woman; the woman revisits places that were meaningful in early life. She returns to her birthplace and rediscovers its astonishing natural beauty. She also discovers the love of a woman for a man, thereby sharing - and intensifying - the wonders of nature. In the process, she recognizes the truth of things she had sensed only instinctively as a child: her kinship with Nature and all living things, the need to honor life in general, and to reorder her own life, restoring its essential human values. Finally, she returns to that special Tree. When she touches it, she is touching Nature. When she finds a child in its branches, she finds not only herself, but future generations of humanity - joined with Nature. All at once, she has reached back to the past and out to the future: in doing so, she reaches Beyond Time.”

Philosophically, the film tells us that “man belongs to the earth… but earth belongs to God, not man. It is an earth we have no rights to, only privileges… and a responsibility to save - not time - but earth itself, for those who follow in time.”

Encapsulated as it is, of necessity, it still seems to “read” like a feature, after all, unless this is just wishful thinking!

Whatever its eventual format, since most film offerings at world’s fairs are free to the theatergoer, its ultimate fate is not unlike that of any nationally distributed feature film: if it’s good - if it truly entertains - it succeeds, but if it’s a flop, you can’t give it away, even with a bigger “ADMISSION FREE” sign on the front door of the pavilion!

If you’ve attended past world’s fairs, you’ve seen the tendency to surround a film presentation with “gimmickry.” In the ‘64 New York Fair, Eames lifted hundreds of people up into an IBM “egg” to view a 15-plus-screen presentation.

In the United States Pavilion at EXPO ‘67 in Montreal, the designer transported the audience through tunnels, under large projection screens, that swung away as the audience traveled by.

In New York, in ‘64, Francis Thompson proved a point when he kept the audience in a fixed, seated position, and concentrated on the filmic content in his “TO BE ALIVE.” His “gimmick” was to use a 3-part split screen format, using a three-35mm synchronized projection system. The offering won an Academy Award. At Expo ‘67, in a film he made for us for Canadian Pacific Railway (we designed the pavilion and exhibits, and assigned Thompson to make the film), he attempted to capitalize on his Oscar-winning format, and upped the screens to six. The film was called “TO BE YOUNG,” and although nice, never achieved the success that “TO BE ALIVE” did. Part of the problem was in the medium’s overpowering the message - a mistake we vowed not to make at EXPO ‘74 in Spokane, Washington.

We realized that added dramatic effect is desirable, and, as you read on, you’ll see that we had our “gimmickry” too, but the film concept was designed as a single screen presentation, and works extremely well without the special effects. (This is a good thing to keep in mind, for it gives the film extended life if, after the fair, the client desires to use the film for television or as a feature short subject for national distribution.)

(Original Caption) The “Sunbrella” that came with the van protected the film (and camera crew) from the intense heat, but FERCO provided no equipment in the van to combat the rattlesnakes.

ENTER: THE CLIENT. We’ve had major programs with governmental agencies before, and they can get tacky, what with 10 and 20-man committees to deal with.

Fortunately, in this program, the State assigned a small, efficient committee to choose the film producer and exhibition designer, and to furnish them with background and initial direction.

Once the contract was signed, two men were assigned as liaison: one with the State of Washington; the other the coordinator of pavilion design. Again, fortunately for us, both of these men were subscribed to the philosophy that you hire professionals because you want their creative thinking and their experience, and you let them run with the ball.

It was the best-managed governmental program that I can recall.

At one key juncture, in order to gain the approval of the film treatment, it was necessary to present our concept to the State Legislature. The question became, “How do you communicate with dozens of men and women, all with their own points of view and representing, in all likelihood, differing factions within the political sphere of the State, none with film experience or knowledge of the nomenclature of our business?”

We found a formula that is perhaps as close to ideal as it is attainable. First, we built two scale models. One was a model of the pavilion interior, showing in detail the exhibition, ramps and theater. We photographed the model with close-up lenses, and, utilizing a two-screen slide presentation, literally “walked” the Legislature through the pavilion. The second model we fabricated was a box 4x4x8 feet wide, with a rear projection screen and mylar mirrors at either end. We edited down some scenes from an earlier Washington State film, and rear-projected them onto the screen.

Our theater defied verbal description. (How do you explain the concept of a filmic image that expands infinitely… and by using mirrors?) And this, in fact, was what we proposed doing!

(Original caption) Second Unit Cinematographer Charles Groesbeck, positioned precariously in a doorless DC-3 to shoot some dramatic models of mountain peaks.

After an orientation as to the goals of EXPO ‘74 - a “walk” through the exhibit via slides, and a description of the theater - we took a 15-minute break, and permitted all to view the scale model and peek into the mirrored box, to experience the “infinity image” effect.

The key element in the success of the presentation (one perhaps not new, but certainly one that more producers should find an invaluable selling tool) was the use of a magnetic tape recording of the film concept. We produced a 25-minute tape, professionally narrated, complete with music and sound effects. At the proper time, the room was put into complete darkness, the audience was asked to close their eyes, sit back, conjure up their own visual image, and enjoy themselves. It really works! Short of the actual completed film, I have found no technique more effective in selling a film to a large group than letting them create visual images in their own minds. Who can argue with the personal interpretations that one creates for oneself?

The Film Treatment was approved, and we were on our way! (Two years later, when we premiered the film, one of the legislators came up to us at the pavilion to tell us how much he had enjoyed it, and left us with the comment, “It was great… but it was quite different from the film you showed us in your original presentation two years ago!” We had difficulty convincing him that the film he “saw” had only been in his mind. What better proof of the effectiveness of the taped presentation technique?

(Original Caption) The awesome 125-foot spread and 25-foot circumference of this Broad-Leaf Maple tree, discovered after a lengthy search, made it a perfect natural “character” for the film.

THE TREE. Finding the tree was no easy task. We enlisted the help of all the State agencies who might know of such a unique tree; followed every lead. The tree had to look thousands of years old. We literally scoured every section of the state, by car and helicopter. We found two Douglas Firs: one over 200 feet tall, on the Ft. Lewis Gold Course; the other in a lovely little cemetery in Centralia. Both were very dramatic and “cathedral-like,” when one stood under the umbrella of lower branches.

Camera points-of-view were limited by visible signs of civilization - the 9th tee on the golf course, for one, and the grave markers for the other.

(Original Caption) Director of Photography Jack Priestley and Mo Brown check out Grip Marty Nallan’s [green jacket] placement of the camera for a down shot from a branch of the tree.

We locked in on the Ft. Lewis tree, and arranged for the crew to come out in two days. The night before their arrival, Gerry Ehrlich, one of our production assistants (a Washingtonian who was invaluable during the pre-production stages), got wind of an awesomely large tree up in the San Juan Islands.

Ed deMartin, the Director, felt obliged to at least see the tree before production began. He and Gerry, Lou Girolami, the Associate Producer, and Jack Priestley, our Director of Photography, left for the San Juan Islands on the next available ferry from Seattle. Jack shot our film, called “CIRCUS,” in 70mm (see American Cinematographer, February, 1973). I had already set up Olympia as our base for the first shoot because of its close proximity to the tree in Fort Lewis.

That night I got the call… “Bob - this is Lou. The tree is unbelievable! Ed and Jack love it.”

(Original Caption) Lacking a Chapman crane, the company pressed a “cherry-picker” into service for vertical panning shots of the tree. They would have preferred a helicopter, but limited space prohibited its use.

“What would moving the location to the San Juan Islands do to our budget, Lou?”

“Don’t ask,” he responded.

Late that night, upon their return to Olympia, we all met, and studied some 20 polaroids of the tree, taken from all angles called for in the script. It really worked. It was almost a perfect match to the tree deMartin had envisioned in his original concept and in the storyboard.

Lou worked through the night to make accommodations for some 35 people, including crew, talent, equipment, generators and cherry-picker (for tree-panning shots) and their operators, who were sent up in advance, as travel by road and ferry was tediously slow.

I asked Jack Priestley if this was convincing as a place in which “God lived,” as the little girl in the story believed. When he presented me with a polaroid taken of him under the tree, on his knees, in an attitude of prayer, I was convinced!

deMartin and I thought the film would be more “true to life” if we selected our “talent” from residents of the state. This decision created perhaps the most arduous task of the pre-production phase, that of finding five girls who would be perceived by the audience as the same child, growing from a baby to a mature young lady

Once, we thought we were all set, after three months of interviews all over the state… then we did our screen tests. This “acid test” indicated that we were not ready. Further arduous searching and testing finally provided the winning combination!

Working with young children may be the most frustrating experience a filmmaker can have. But when we achieved a usable take, it was like finding gold!

(Original caption) Director of Photography Jack Priestley and crew atop the “Ferco-Van,” which proved invaluable on location. Every square inch is packed with equipment, including Elemack dolly and 50 feet of track and a built-in loudspeaker system.

Another frustrating element of the film had to be the long, seemingly unbelievable wait to see dailies. Since we spent a good portion of the shooting in the “boondocks,” sometimes ten days would pass without seeing a daily. Scheduled airlines were almost totally incompetent; chartered planes were slightly more efficient. We were totally in the hands of Priestley, who was uncompromising in his insistence on near-perfect light conditions when shooting. His persistence paid off. The dailies were magnificent. We never pushed the film once, in processing. When the first cut was complete and a slop print produced, it was the closest thing to a balanced print I had ever seen.

Shooting in anamorphic created a few problems, too. (See Grosebeek article, this issue.) We carried our own anamorphic lens with us for those occasions when we were in a town without anamorphic projection facilities to screen dailies. The Todd-AO anamorphic camera system was used to photograph the film. This wide-screen format was chosen for two reasons: the oversized format lends itself to the lovely panoramic vistas prevalent in the film, and the immense screen was ideal for the unique custom designed theater, which I will discuss in greater detail later.

Although it is not mentioned here, deMartin actually got his urban footage for ‘About Time’ in New York City, telling a New Yorker reporter that “we can’t get what we need in the West, so we’re getting our shots in New York.” (The New Yorker, September 24, 1973)

In the first act of “ABOUT TIME,” we went to great lengths to achieve a primeval quality on film. This act, after all, established Earth “before time”; that is, before man was present. It was important to achieve a smooth transition from scene to scene, representing Earth’s natural beauty, not yet cluttered by man’s intrusion.

We swept from crashing waves on a beautiful, desolate beach, the camera pushing through the mossy jungle of the Hoh Rain Forest on the Olympia Peninsula, to a shot of an eagle soaring high over the Cascades, and ended up on a pan down our glorious old tree. We had to travel some 2,000 air and land miles to get the contrasts, but it was all accomplished within the boundaries of the state. Does the average movie-goer realize what it is like to accomplish on film that which is visually “smooth” and cohesive?

We had decided on shooting hermit crabs, starfish and the other inhabitants found only in the tidepools of the Northwest, at Neah Bay. Girolami had made arrangements with a resident archaeologist, who had befriended the local tribe of that farthest outpost of the Continental United States. He had discovered a longhouse that proved the tribe’s genealogy back over 2,000 years, and had become the tribe’s liaison with outsiders. The tidepools hold religious significance for the Quilutes, and it was an honor for white men to be allowed to set foot near them.

Our advance guard, usually one or two days ahead of the crew on the itinerary, found to our dismay that a bad weather front had set in at Neah Bay, and that no sunlight was expected for at least a week.

(Original caption) Grosebeek hand-holding a 35mm Arriflex with heavy anamorphic lens to capture close-up footwork of skiiers.

We needed a location for our shoreline and tidepool scenes, and discovered an alternate location in La Push, further down the northwest coast of the Olympic Peninsula, 15 miles outside a little logging town, called Forks. Indian guides of the tribe showed us the access routes down the steep slopes to the coast. A few trips (about one mile, round-trip, from the nearest road to the shore) had us all heaving for breath.

Marty Nallan, key Grip, said, “Forget it - no way to honcho all this equipment down and still have enough energy to make shots.” I agreed.

Girolami, my Associate Producer, started looking for a helicopter, and found one in a nearby town. The helicopter pilot’s schedule was booked solid in forest fire fighting and spraying activities. After much debating, he deferred to our request, and squeezed us in between fire, having caught the “movie-maker’s bug.” Six trips back and forth from the airport got crew, equipment, and talent on the beach by 7:00 a.m. each morning. We got great footage of the crashing waves there, and simulated our own tidepool with “imported” sea animals from Neah Bay!

(Original caption) Custom projection booth, housing two Norelco DP-75mm projectors, modified with new Christie xenon quartz lamp housings, with horizontal light source for better screen illumination.

I have to say, I got a small taste of what cinematographer Robert Surtees meant when he referred to “terrible experiences filming in Washington on ‘LOST HORIZON’.” (See American Cinematographer, April, 1973.) However, we were probably the first Production Company to enjoy good shooting weather in Washington most of the time. Gerry Ehrlich and John Cox, Production Assistants, who had made several films in the state, kept shaking their heads in disbelief whenever I complained about the sun poking itself behind a cloud for a half-hour. Apparently, we were having unbelievably good luck, and were too naive to realize it.

But, in the final analysis, we attributed our good fortune to Jack Priestley, who wore his “Location Shoes” every day. His footwear (we’re giving them the benefit of the doubt in calling them “shoes”) were a pair of size 14, Kelly-green and white striped suedes, with a grossly large Shamrock stitched on the side of each! Jack claimed supernatural powers were invested in them, guaranteeing sunshine in all outdoor locations. (One morning, Jack came to the location sans “green monsters.” We sent the driver back to the hotel for them. Why spit in the eye of fate?)

Priestley, an imposing 230 pounds of he-man, who has filmed many action films, showed that he is also a cinematographer with sensitivity. When we were in the Hoh Rain Forest, shooting some of the “Before Time” sequences, Jack got all turned on with the natural beauty he saw in the eyepiece of a super ECU of a mushroom through the Macro lens, topped off with a few Proxars, to bring us in even closer to the subject. He insisted that the whole crew look through the eyepiece at this little natural jewel. Marty Nallan, veteran of many film wars, was not turned on by the static set-up and commented, “Yeah, Jack, just like shootin’ ‘ACROSS 110th STREET.’“ It broke the crew up.

(Original caption) The rear-projection screen, as seen from the lower viewing tier. The screen is made of a custom-extruded plastic material, produced especially for this theatre by Harkness Ltd., London. The one drawback of the rear-projection system was the tremendous amount of space lost in providing a 100-foot image throw from the projection booth to the screen.

THE EXHIBITION. In producing a film for an International Exposition, it is often wise to offer the visitor more peripheral excitement and involvement than is possible in a standard theater.

We decided to create a total physical environment, related to the ecological theme of the Fair, but more importantly, to establish a mood for those about to see our film.

A dramatic network of ever-curving ramps was created, by which to bring the visitor from grade level up to a height of 24 feet. Three hundred people are “loaded” into three ramps; 100 per ramp. The destination is the Presentation Theater at the end of the ramp network. As the visitor ascends the ramp, he literally walks through a “sight and sound” show, where he experiences the forms of nature: the sun, rock formations, vegetation, waterfalls, etc.

At the end of his journey, he finds himself at one of three holding areas, immediately outside the theater. A large, digital clock is on display, “counting down” the minutes before the next film presentation. At “zero hour,” the theater doors open on three levels, and the viewer enters on one of three vertically stacked tiers: the lowest at grade level; the highest at 24 feet above grade.

Because of the high visitor volume normally experienced at world’s fairs, Alex Cranstoun, my partner, in charge of Exhibition Design, elected to utilize a “locked” traffic pattern; that is, one in which the visitor, unknowingly, is always moved in a specific direction at a specific time. Thus, while entering the theater from the left, he leaves from the right, and there is a logical, continuous flow of traffic in one direction.

THE THEATER. Just being in the theater is, in itself, quite an experience! Three hundred people are literally perched, like eagles, on three vertical tiers, one above the other, so that everyone has, essentially, a first-row seat.

Although the film was designed to work in a standard theater configuration, we decided to “zap up” the World’s Fair presentation strategically, by lining the side walls of the theater with floor-to-ceiling mirrors, running the full 40 feet from the edge of the screen to the edge of the viewing tiers.

The mirrors are hidden by black curtains, and these curtains are automatically withdrawn at key moments in the film, to reveal the mirrors to the audience. This was made technically possible because the film is rear-projected, providing a cleanly-delineated intersection between mirrors and screen. The effect, when the mirrors are exposed, is such at the images seem to explode on the screen, and literally stretch left and right, as far as the eye can see.

Of course, those scenes of the film seen on the central screen when the mirrors are exposed had to be carefully designed to look well when flopped, for the mirror-image system accomplishes the infinity effect by flopping every other multiple of the actual image on center screen. The effect is truly awesome, when we realize that the audience is only 40 feet away from a screen that measures 23’ high by 50’ wide. The viewer is literally in the film!!!

THE SOUND TRACK. With up to six sound tracks available to us on the 70mm show prints, we had an opportunity to envelop the audience in super-stereo for maximum effect.

A good portion of the success of “ABOUT TIME” must be attributed to the original musical score and arrangement of David Lucas and Tom McFaul, two young musical geniuses in New York City, who are currently enjoying tremendous success. Lucas is the “pop” specialist. McFaul, of classical background, has the talent to adapt the “grand sound” of the classics to a contemporary idiom. They reviewed the rough cut and were “immediately turned on.”

The score runs the full range - from the semi-classics of a flute solo, to the grandeur and brilliance of a 50-piece symphonic orchestra; from the solo voice of a folk singer, to the up-beat sound of a children’s chorus.

This producer was correct in thinking David Lucas and Tom McFaul were going places. When they created the soundtrack for “About Time,” their partnership had only just begun - but before long, they had given the world a plethora of memorable tunes, including the Meow Mix theme, “Catch the Pepsi Spirit,” and AT&T’s “Reach Out and Touch Someone.” David Lucas also produced Blue Öyster Cult’s “Don’t Fear The Reaper,” although Saturday Night Live identified the producer as Bruce Dickinson (played by Christopher Walken).

In my opinion, Lucas/McFaul are the hottest musical entries in the film business of the decade.

Music recorded on 16 tracks was mixed down to 4-track, and this, with all stereo effects, narration and singing, was turned over to Lee Dichter, of Photo-Magnetic Sound, who is probably the best multi-channel mix man on the east coast. He developed a 4-channel crossover speaker system for the mix, so we would hear the final mix against the image, exactly the way it would be seen and heard at our pavilion. I believe it’s the only set-up of its kind in the east.

Armand Lebowitz, of Lebowitz Films, an editor and now dear friend, dedicated himself to the task of a 20-minute film from enough footage content to make a film of much longer running time. He stayed with Ed and me through every phase of recording and mixing, contributing all the way. Armand reminds me of an atomic reactor, somehow concealed in a human frame: when running rough-cut footage, he supplies all music, sound effects, and narration verbatim as he stands before his “Cine,” working the levers and levels, like a maestro standing before his orchestra with the baton.

During all of these post-production activities, Don Kloepfel, projection systems consultant of Hollywood, was busy designing a customized projection system for the theater, including custom lenses for the DP 75’s, to meet the unique problems that are encountered in using a wide-screen, rear-projected format.

The combination of the extruded plastic Harkness screen and Don’s optics, gave us a rear-projected image that matches the quality of any front-projected, standard theater configurations.

Don also designed the programming equipment that automatically cued the houselights, curtains and lamp douser off a low-frequency signal on the fifth sound track of the print.

Don is “Mr. Reliable.” We’ve thrown some tough assignments at him in the past, and he always comes through.

All post-production phases complete, we previewed the answer print for the client at MGM Laboratories in Culver City, California. Lyle Burbridge, a real pro, showed tears, and said, “I think I’ve been looking for that tree all my life.” It was a wonderful reaction, and one we all valued dearly.

Now that our mini-feature, “ABOUT TIME” is complete, Ed deMartin and I find it has done nothing less than sharpen our appetites for our next project - hopefully, a full-length feature!

As part of the design firm DMCD, Ed deMartin and Robert Marona continued to create “interpretive exhibit design” projects for entities like planetariums, museums, and the Nixon Presidential Library. The total cost for their Expo ‘74 exhibit concept, including the film, was $1.9 million.